Early Life

Paik’s career began in music. Born in 1932 to a wealthy family of textile manufacturers, Paik trained as a classical pianist in Seoul before fleeing to Japan with his parents and siblings upon the outbreak of the Korean War. He enrolled at the University of Tokyo, where he wrote a thesis on the German composer Arnold Schoenberg, then moved to West Germany to pursue graduate studies at Munich University. An electrifying encounter in 1958 with the composer John Cage inspired Paik to incorporate objects, theatrical interruptions, and pre-recorded sounds into his compositions. Termed “action music,” works like Étude for Pianoforte (1960)—which concluded when Paik leapt into the audience and cut off Cage’s tie—caught the attention of artists like Karlheinz Stockhausen, who wrote a part for Paik in Originale (1961), and George Maciunas, who invited Paik to join Fluxus. In 1964, Paik moved to New York, where he met the cellist Charlotte Moorman. The pair embarked on a decades-long partnership that generated performances including Variations on a Theme by Saint-Saëns (1964) and Opera Sextronique (1967), during which they were arrested for indecent exposure.

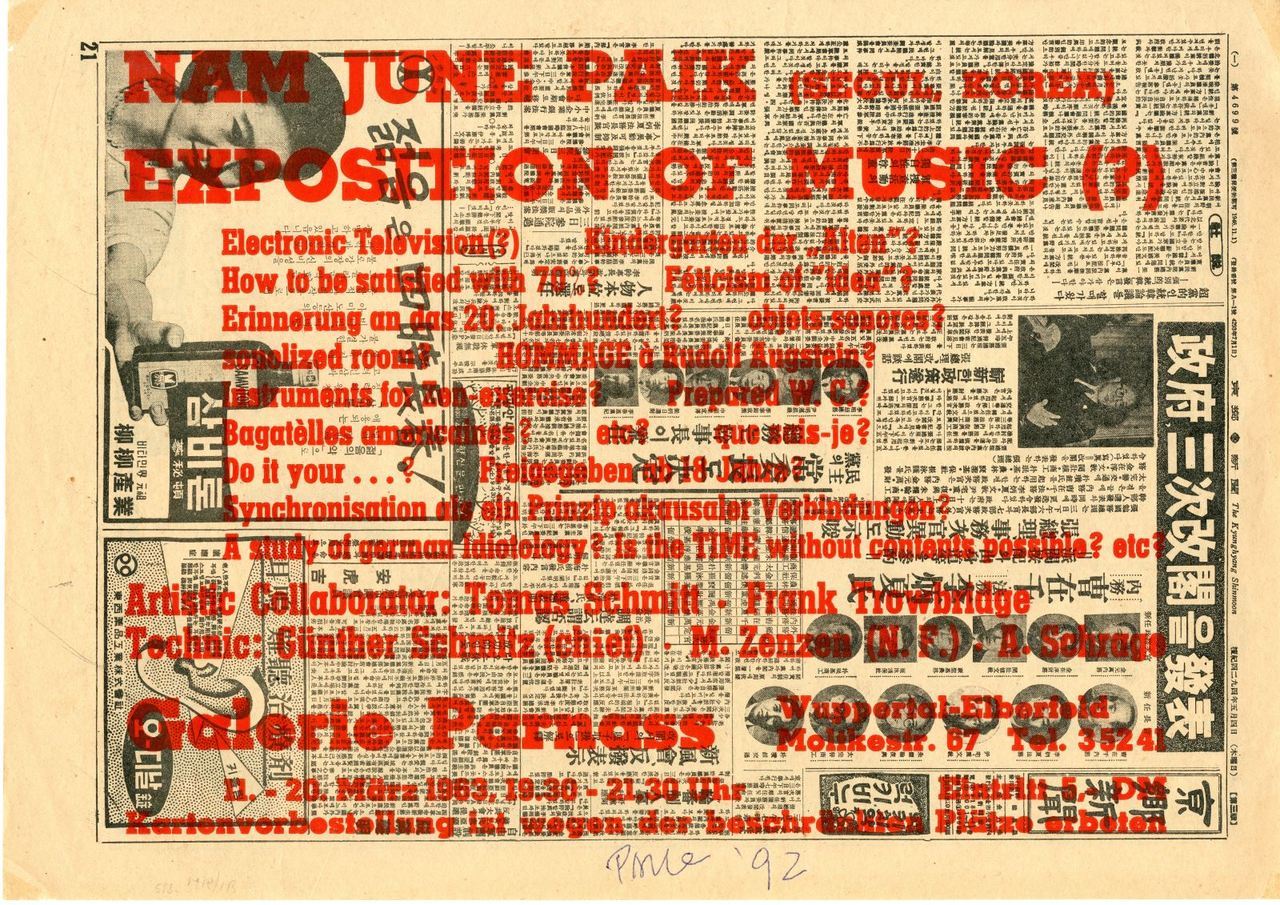

Exposition of Music

Paik held his first exhibition in 1963-a seminal debut, entitled Exposition of Music-Electronic Television, at Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal. This marked the beginning of his transition to inventor of a new art form, which utilized Fluxus philosophies and also introduced television as a viable instrument. In the exhibition, thirteen televisions, representing individual pieces, lay on their backs and sides with their screen images altered. For example, Zen for TV (1963) reduced the television picture to a horizontal line while Kuba TV (1963) shrank and expanded the image on the television set according to the changing volume. The exhibition was also remembered for Joseph Beuys's participation, after he took an ax and smashed Paik's installed pianos into pieces.

Beginning of Video Art

It was in New York in 1965 where the first piece of so-called "video art" was created when Paik claimed his video footage of the Pope's visit to be a serious artwork. The footage was shown, later on the day of its capturing, at a screening at the Café A Go Go in Greenwich Village. Albeit grainy, it proved a revolutionary new way to consider art.

In 1969 during a residency sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation at the Boston public television station WGBH-TV, Paik was finally able to realize his dream of freely altering video image by successfully constructing a video-synthesizer (with Shuya Abe's assistance). The Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer transformed electronic moving-image making, as it was one of the earliest machines that allowed the artist to manipulate existing videos, combine images from multiple sources, and shape the TV canvas like a piece of artwork.

Robotic Art

In the early 1980s, Paik returned to his earlier interest in cybernetics and robotic art, and created his first series of video sculptures, which epitomized the humanization of technology. One of Paik's rare talents was that he seemed to always be one step ahead in predicting through his artwork the role that rapidly progressing technologies would have within society. One illustration, his Family of Robot, portrayed a benign relationship between the family unit and technological advancements. It was created during a time when Americans were becoming more comfortable with technology as an integral part of their daily lives: tvs, video games, and camcorders populated many homes and, by 1983, the first mobile phones became commercially available. Family of Robot initiated Paik's ongoing series of humorous and engaging robot portraits through the 1990s, many of which were based on historical figures, such as Genghis Khan and Li Tai Po, or his friends including John Cage and

Paik's hybrid mix of media and the way he linked countries, cities, the avant-garde movements, and popular culture through his satellite productions manifested his utopian and democratic pursuit of cultural, economical, and informational connections and exchanges across the globe without borders.

Later Life

The aging artist developed much of his late work in dialogue with his studio assistant, Jon Huffman, who remained at his side. Ken Hakuta, Paik's nephew, who visited and lived with him in Manhattan in the 1960s, came back after Paik's stroke to bring the artist's home into financial order and to create a secure and sustaining living environment for his final years. Paik died in Miami in 2006.

In 2009, the Smithsonian American Art Museum acquired the Nam June Paik archive, which includes objects (recordings, vintage electronics, and other source materials) and paper holdings (the artist's early writings on art, history, and technology along with performance scores, production notes, and plans for video installations). His major posthumous retrospective, entitled Nam June Paik: Global Visionary, was also mounted at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2012-2013.

The Legacy of Nam June Paik

Nam June Paik's enormous contribution to the history of late-20th-century art largely stems from his position as the first major Video artist. His groundbreaking exploration and use of modern technologies laid the foundation for a new generation of artists in today's complex media culture. Now media arts are pervasive across the international art world as artists continue to use a mix of film, video, digital media, and the Internet to create work that is visible in museums, galleries, art fairs, online, offline, and everywhere in between.

Remembered as the "father of video art," Paik left behind a remarkable legacy to subsequent generations of artists including and others who explore the potential of videos. Paik's influence is perhaps best described by the contemporary American multimedia artist Jon Kessler: "Paik laid the groundwork for artists like me who play with the apparatus and mechanisms of the medium, turn it in on itself, and come through the rabbit hole still believing that it's possible to make engaging, playful, and serious work."

The ideas of cultural free trade that Paik wrote about and championed have been made manifest through the birth of social media and sites such as YouTube where today's artists can distribute their work freely to an international population.