One of his seminal installations, illustrates Paik’s profound grasp of technology’s capacity

for composition and the new aesthetic discourse that he helped to create. To enter the

piece is to experience an uncanny fusion of the natural and the scientific, as hidden amid

an undergrowth of live plants are video monitors of various sizes. All are playing the artist’s 1973 collaboration with John J. Godfrey, Global Groove, which montages performers from around the world into a gyrating visual mix, and the videotape’s sound track serves as musical and spoken counterpoint to the monitors’ flickers of light. TV Garden set a new standard for immersive, site-specific video installations. Restaged for the artist’s exhibition

at the Guggenheim Museum in 2000, its influence can be seen decades later in ambient, room-sized installations by such artists as Gary Hill and Bill Viola.

TV Garden seeks to tease the senses with a mixture of color and sound. Color from the

lush tropical garden makes the canvas for his TV sets. Sound emanates from the TV sets

and rustles through the leaves of the various plants that the television sets are nestled among.This artwork grabs the eye and the mind in its juxtaposition effect, where the

viewer’s attention moves from plant life to television sets and vice versa.

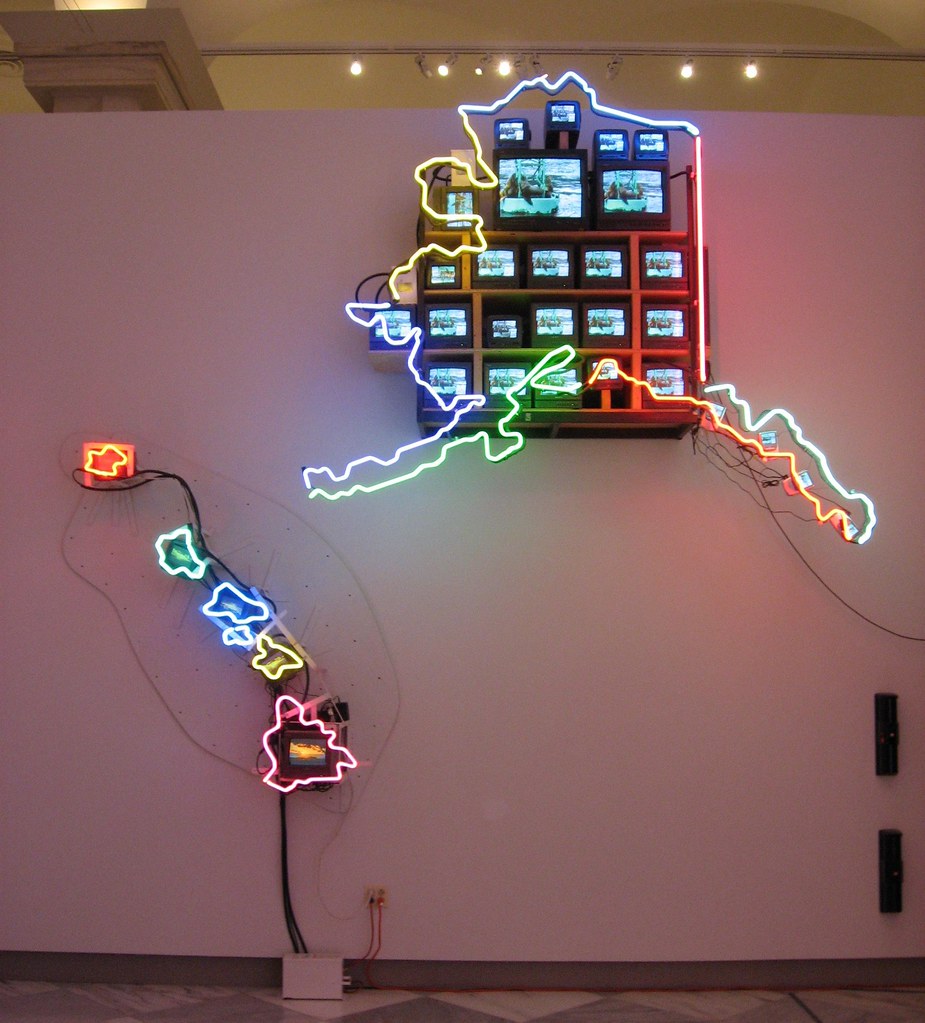

When Nam June Paik came to the United States in 1964, the interstate highway system was only nine years old, and superhighways offered everyone the freedom to “see the U.S.A. in your Chevrolet.” Walking along the entire length of this installation suggests the enormous scale of the nation that confronted the young Korean artist when he arrived. Neon outlines the monitors, recalling the multicolored maps and glowing enticements of motels and restaurants that beckoned Americans to the open road. The different colors remind us that individual states still have distinct identities and cultures, even in today’s information age.

Paik augmented the flashing images “seen as though from a passing car” with audio clips from The Wizard of Oz, Oklahoma, and other screen gems, suggesting that our picture of America has always been influenced by film and television. Today, the Internet and twenty-four-hour broadcasting tend to homogenize the customs and accents of what was once a more diverse nation. Paik was the first to use the phrase “electronic superhighway,” and this installation proposes that electronic media provide us with what we used to leave home to discover. But Electronic Superhighway is real. It is an enormous physical object that occupies

a middle ground between the virtual reality of the media and the sprawling country beyond our doors.

Exhibition Label, Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2006Nam June Paik is hailed as the father of video art and is credited with the first use of the term “electronic superhighway” in the 1970s. He recognized the potential for people from all parts of the world to collaborate via media, and he knew that media would completely transform our lives. Electronic Superhighway — constructed of 336 televisions, 50 DVD players, 3,750 feet of cable, and 575 feet of multicolored neon tubing — is a testament to the ways media defined one man’s understanding of a diverse nation.

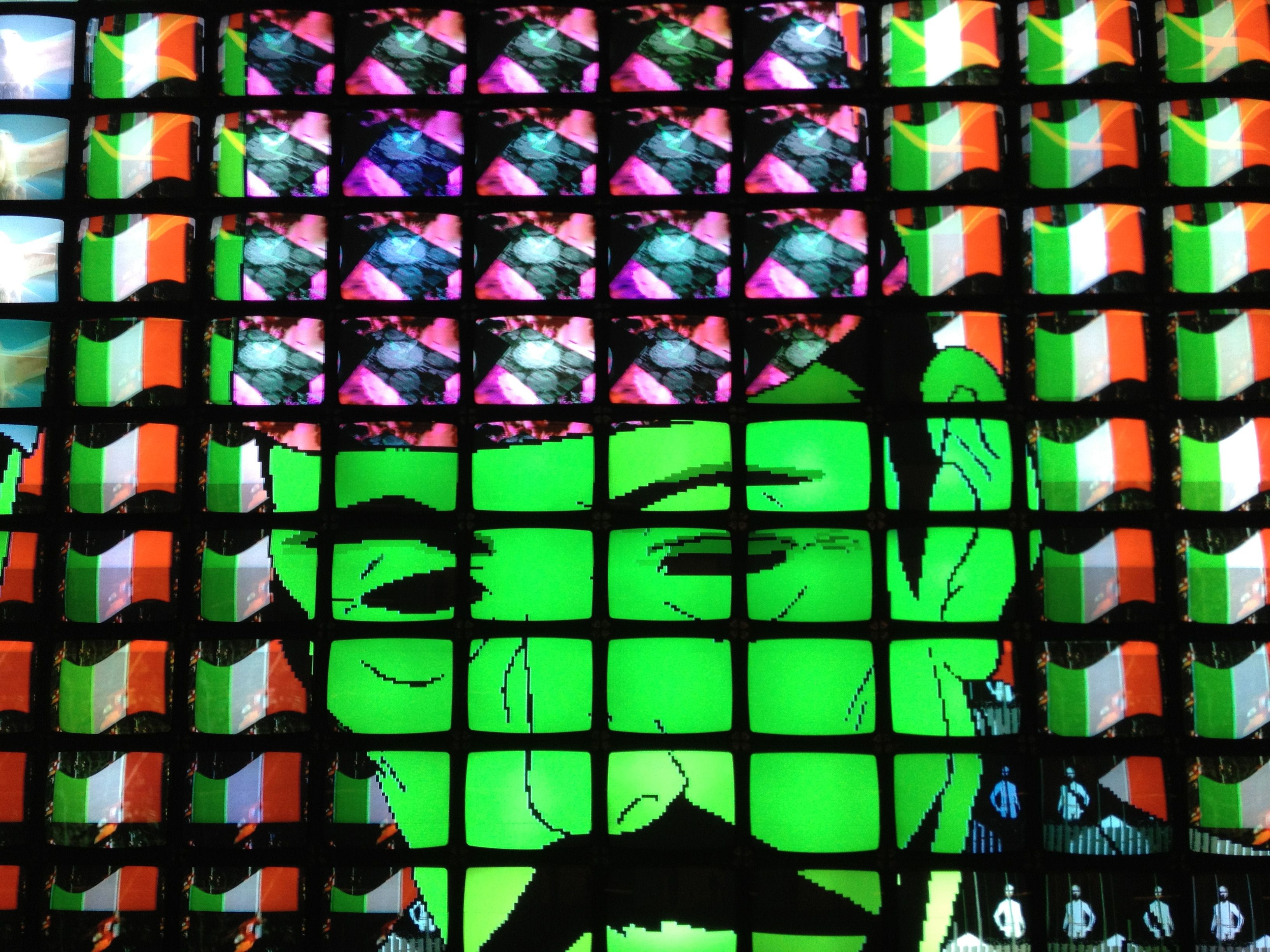

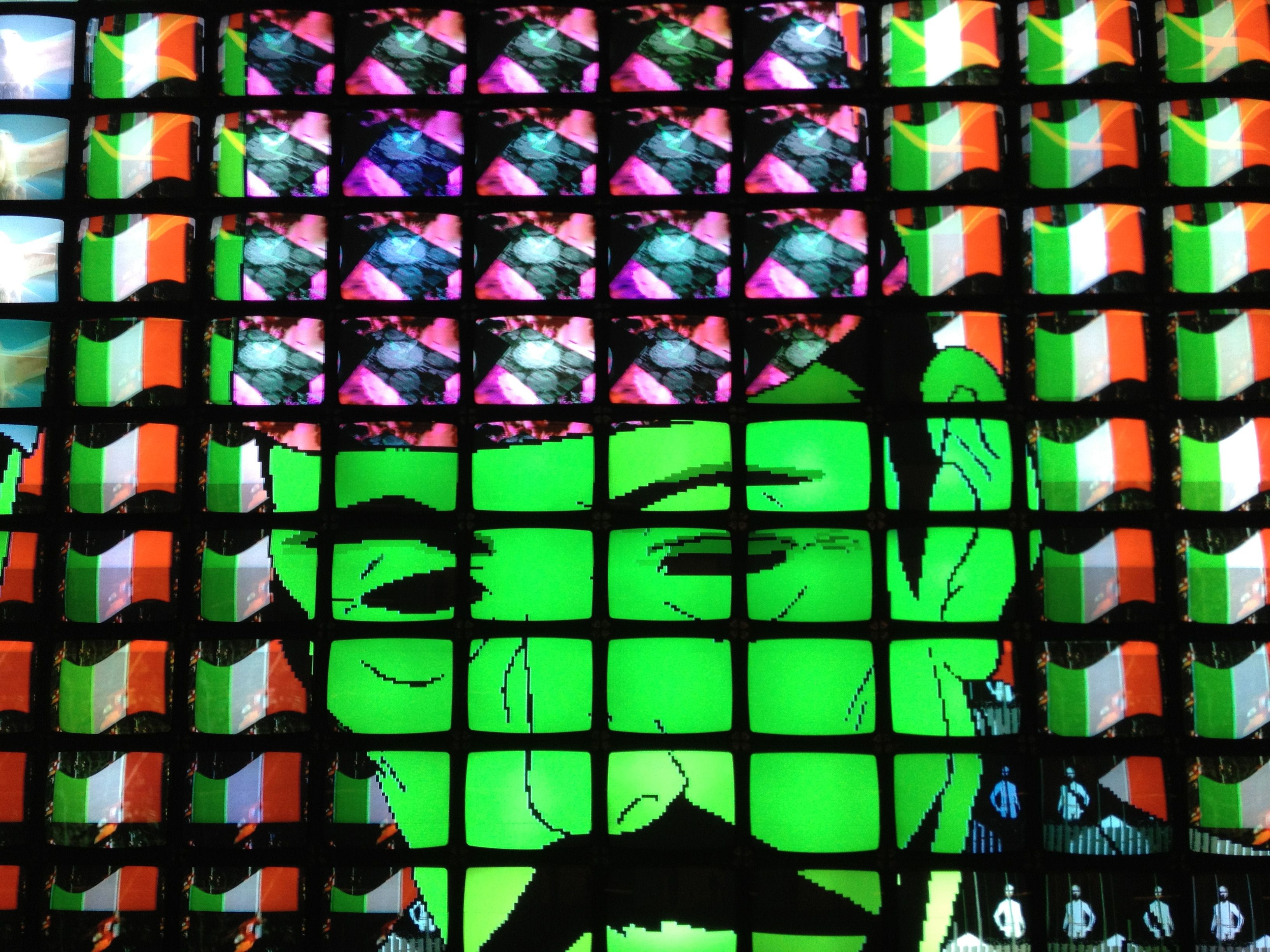

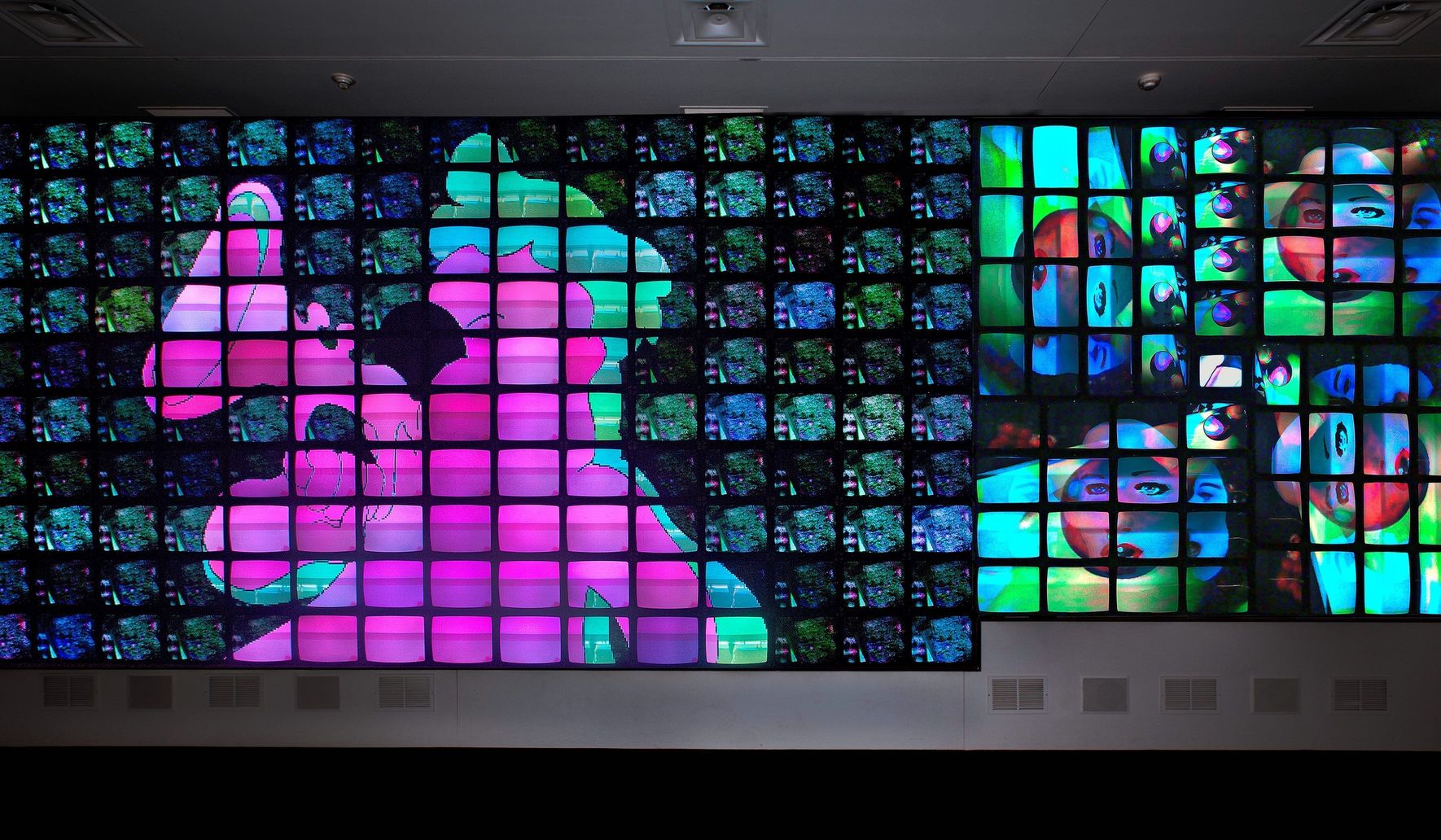

Megatron Matrix is roughly the size of a billboard and holds 215 monitors. The videoaugmented

by a loop of unrelated soundbitesmixes images from the Seoul Olympics with Korean folk rituals and modern dance. Smaller clips play simultaneously on multiple monitors, while larger, animated images flow across the boundaries between screens, suggesting a world without borders in the electronic age.

Paik sorted the monitors into two distinct sections. The Megatron conveys the vast reach of the media, while the smaller section, the Matrix, emphasizes the impact on each of us. In Matrix, Paik arranged the monitors so that the images seem to spiral inward around a lone screen showing

two partially nude women. He may be suggesting that our bodies are our primal connection to the world, but the effect on the viewer is of being assaulted by “too much information.”

In the early 1960s, Paik began incorporating televisions into his collaborative performance pieces with American dancers, musicians, and artists. Today, the fusion of pop music, commercial culture, and nationalist symbols captures Paik’s story and that of millions around the world. Paik’s prophetic awareness of the power of television has been borne out in our “plugged-in” age, when any kind of art or entertainment is available on our screens all the time.

Mirage Stage is a reference to theatrical stage-sets, not only because of its structure and layout but also because of its monumentality and frontality. The loss of stage-limits, so central to Nam June Paik’s performances in the 1960s, is given a further twist in “mirage stage” so that it now becomes a ‘global groove’, which the artist alludes to through a bombardment of images from multiple screens. This is an endless saturated rapid-fire collage of images taken from his main works in mono channel video: A Tribute to John Cage (1973-1976), Merce by Merce by Paik (1975-1978), Documenta 6 Satellite Telecast (1977), Guadalcanal Requiem (1977-1979) and a significant amount of Global Groove (1973), an unbroken line of banal commercial images mixed with choreographies of Merce Cunningham and performances featuring Charlotte Moorman, with which Paik communicates the complexity of an increasingly interconnected and interdependent world. All of this taking place in a silent, soundless environment, which strengthens the idea of mirage and unreality. Paik appears to be referring to the new art regime, under cultural industry and global capitalism, where the boundaries between art and entertainment, between information and spectacle, become blurred. This installation exemplifies a later production which emerged as a result of Paik and Shuya Abe’s collaboration on TV synthesizers.

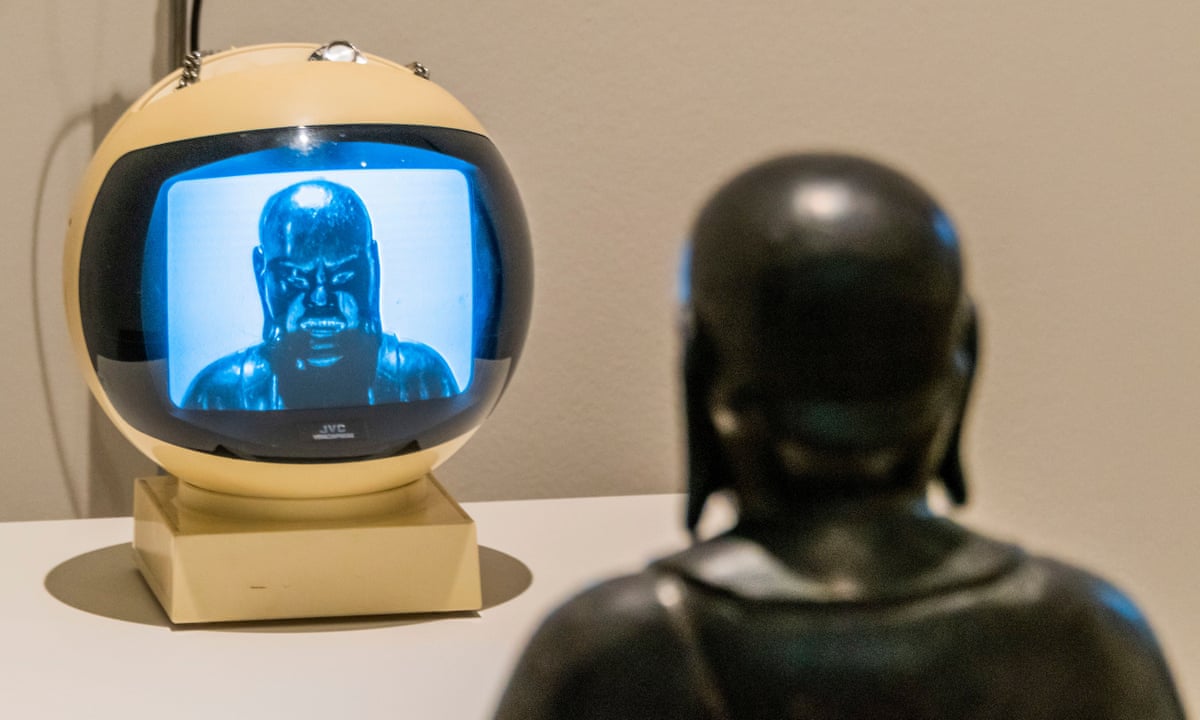

This renowned artwork by Paik depicts a sculpture of a Buddha from the 18th century posed with a symbolic hand gesture called mudra which is for tranquil meditation. A video camera is placed in front of the Buddha, recording the statue while playing this projected image on a white TV screen that looks futuristic. This work induces the feeling that the Buddha is doomed to be forever caught in the closed-circuit loop that is the infinite play of his reflection on the TV screen.

This installation highlights the difference between East vs. West and pits modern or futuristic elements vs. historical. It also encompasses other themes such as the hold of screens on society and displaying issues such as religion and history on screens. Paik succeeded in juxtaposing modernization and emerging technologies with religious and historical themes in his society and encoded these messages in the form of images into the installation.

The installation also conveys the vanity of modern times with the Buddha contemplating and absorbed in his own image like society’s self-absorption, which is driven by the media and technology. Another message that the installation conveys is that of surveillance. With the Buddha watching himself and the audience viewing the art installation, Paik shows the constant surveillance fueled by technology and the media. Therefore, he succeeded in using art as a code to convey specific messages to audiences.

In 1966, Charlotte Moorman (US, 1933–1991) and Nam June Paik (South Korea, 1932–2006) mailed some promotional materials to the Walker Art Center’s director Martin Friedman, hoping to secure

a Minneapolis venue for their program of New Music and mixed-media performance. The letter, quoted above, emphasized their mainstream credentials—both were classically trained musicians, Moorman a cellist, and Paik a composer and pianist—as well as the daring originality of their work, which had been enthusiastically received by avant-garde audiences in the US and Europe. It ended with the playful passage above, which hints at the humor that infused their two decades of work together.

In TV Cello, Paik took the idea of performative sculpture further. This piece was also constructed from television picture tubes encased in Plexiglas boxes, and its screens were meant to show broadcast TV, prerecorded tape, or live, closed-circuit images, all of which could be manipulated

by Moorman. But TV Cello, a proxy for Moorman’s traditional cello, was also a functioning musical instrument. According to Moorman, it was “the first advance in cello design since 1600.” It had strings, tuning pegs, a bridge and tailpiece, and even a rudimentary peg, just like a standard cello. The strings, however, were amplified and produced crashing electronic sounds when she played it.

During the 1970s, Moorman performed with TV Bra and TV Cello dozens of times, in venues ranging from museums and galleries to shopping malls and community centers. Both objects perfectly melded her brilliance as a performer with Paik’s artistic goal to “humanize technology.” They are also singular works in the history of interdisciplinary art: unprecedented fusions of sculpture, moving image, live performance, sound, and popular culture that blurred the lines between Moorman’s body and Paik’s artwork.

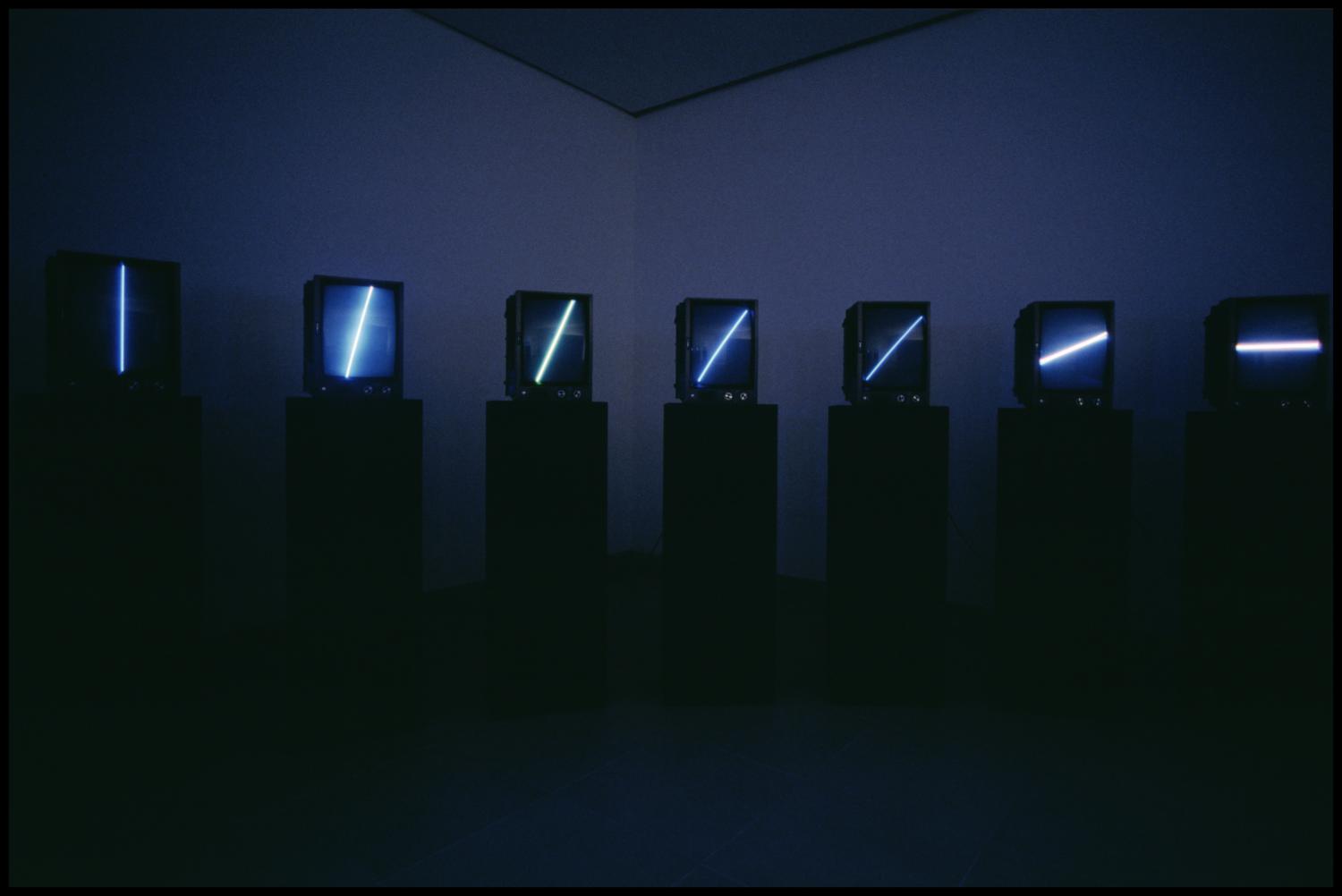

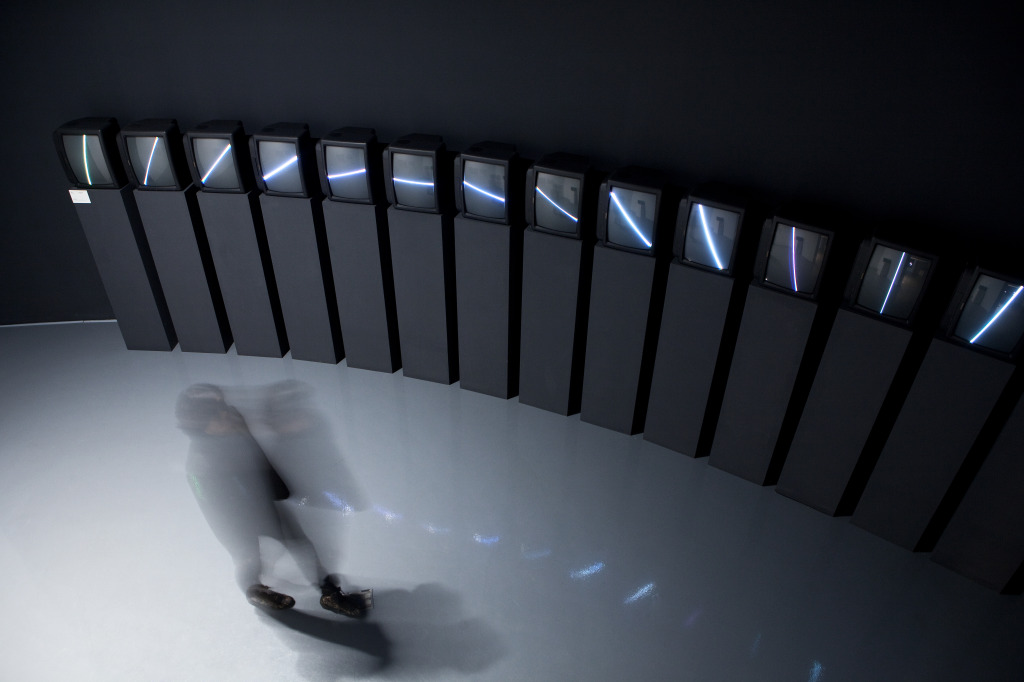

Nam June Paik’s T.V. Clock transforms time into a sculptural electronic object. In this seminal work

of art, Paik rendered the hours through a single line drawn in electric light on a modified TV screen. Paik’s minimal electronic mark, which is tethered to the sophisticated and global apparatus of TV, unleashes a host of ideas about our shared experience of time, through technology, space, cultures, and connectivity. Nam June Paik exhibited many versions of T.V. Clock.

Paik’s TV Clock, one of SBMA’s most important media art works, is on view for the first time in nearly a decade. TV Clock consists of 24 color televisions mounted upright on pedestals that are arranged in a gentle arc and displayed in a darkened space. Paik created each electronic image by manipulating the television to compress its red, green, and blue color into a single line against a black background. Called a "fixed-image television" by Paik, each TV does not involve a videotape, disc, or computer chip but an image the artist created by ingenious manipulation of electronic elements. Read in sequence, each static line tumbles into the next to form a dynamic yet elegantly spare rhythm that resembles a universally recognized way to measure time. A crucial work in Paik’s long career, TV Clock offers audiences the chance to experience the art and thought of one of the 20th century’s most innovative and enduringly vital artists.

The 24 monitors symbolizing 24 hours a day and each monitor showing inclination the line in expressing time. This becomes feasible to remove inducement device of tube in TV and a line

image visualized. 24 color TV monitors, this work convey the passage of time in the most peaceful atmosphere through meditation.